Kaipo Kekona

Kaipo Kekona and Rachel Kapu, photographed at Ku’ia Agricultural Education Center by Angie Diaz

Take a topographical look of any of the construction developments in Lāhainā that started in the past 20 years and you'll see real quick that it's built beyond our needs. It's built beyond what we as an island can manage. The men, the humans are eating the land. So maybe not wai ai 'āina but kanaka ai 'āina. When the people eat the land, we're not caring for it.

We caught up with Kaipo on April 20, 2021, a little over a year into the Covid pandemic and prior to the surge of the Delta variant.

My name is Kaipo Kekona, I'm 38 years old. I was born and raised here on Maui in Lāhainā. I now manage a 12.5 acre farm site known as Ku'ia Agricultural Education Center in the ahupua'a of Ku'ia on Legacy Lands of Keli'i Kulani. Part of our mission for our site there is to not only reclaim space as a native historical food property, but also introduce to our community the practices that would encourage a healthier food system and soils for us to be maintaining in our community. We also hope to fulfill demands in our schools and our senior citizen centers and housing. That's what we want to be able to provide. We also have put aside spaces for people in our community that share an interest to begin a farming spot there, and we make this all possible through a collaboration with the Hawai'i Farmer's Union United, with their foundation, 501c3 nonprofit arm, and Kamehameha Schools, the owners of the property where we are located. I am the Chair of the Lāhainā Chapter with the Hawai'i Farmer's Union United.

I also serve as Po'o for the Aha Moku Ka'anapali Council for the district of Ka'anapali Moku that goes from Pu’u Keka'a to Makamaka'ole. In this position, we advocate for generational resource management practices, and in that manner, we identify different resources methods that we need to consider, implementing more traditional management practices. I also donate my time here at Na ‘Aikane o Maui's Cultural Center. That's my own little side passion; I am a father of four children as well.

Going back a year ago, to pre-COVID times, can you walk me through what was happening and share a little about your experience as the pandemic unfolded?

So for us, back when life was what life was before COVID, (I'll never be able to say life is regular), but when life was what it was, as far as what I do with ag and culture and traditions we always felt like we were on that tipping point where you're either gonna move forward and save it and restore, (I'm not even sure restore is the proper word) or fall the other way and lose it all. That was life in itself. The more we decided to just stay in the path that we were in, the more we would continue to lose. So, we always were trying to make the effort of consciously choosing our path. I think we're all on a path that we don't pay much attention to, and then when we do pay attention, we realize really quickly, that we want to get off of that path.

So, I've been farming before COVID, and I found myself in the agricultural department or industry since I was in high school, picking pineapples and working on farms on the Big Island when I stayed there for about two years. Always farming and always with the same mission to try and learn how to grow good, healthy food and feed our community. I got the opportunity to farm at Ku’ia, we made those efforts and we were working with the schools and doing large-scale volunteer programs.

We utilize organic growing practices, you know, regenerative farming practices, taking the effort to collect indigenous microbes and put that back into the soil to help facilitate that healing process for our soils before planting. That's what we were doing; that's what our mission was. And then COVID hit.

Bouncing back, we're taking in all those old sayings that you hear when you're a kid growing up, you know, "it's not about how you fall, it's about how you get up."

Mind you, we also went through a few natural disasters in this short timeframe as well. Hurricane Lane came through in 2018 and we had a huge fire in the middle of the night. We lost a lot of acreage and our farm got totally scorched and burned away and we were only a year in. Bouncing back, we're taking in all those old sayings that you hear when you're a kid growing up, you know, "it's not about how you fall, it's about how you get up." I mean, we couldn’t give up, this was a challenge, so we'd go at it again.

Then in March 2020, COVID struck. We stopped all our programs, obviously. Now our farm is down to being operated by just three of us with no volunteer help. Volunteers are our big thing. I don't even like calling them volunteers, It's everyone's farm at that point because you come and work on it and it's designed to be for our community. So, if you're from a community and you're working on that farm, it's no longer the educational site, it's your farm. When people show up to work with us, it's a big difference. It's a big help and we lost a lot of that. So, we found ourselves trying to find avenues where we could still fit in. We appreciate being with, helping, and working with our community. When that was taken away, we were like, well, what are we going to do for our community? They're always there for us. How are we going to be there for them, even more now?

Na ‘Aikane at Maui Cultural Center in Lāhainā, photographed by Angie Diaz

A lot of our farmers didn't know what to do with the excess food that they had while at the same time adjusting to the loss of income.

So, we started working with Na ‘Aikane at Maui Cultural Center and they had a program going with QLCC, Queen Lili'uokalani Trust. And they were doing CSA boxes and we were gathering produce through different farms and stores, and distributing boxes to our community. So, I took on from Honokōwai to Honokōhau, and distributed boxes throughout that area. We did that for about six months, just that program. That was one adjustment. We also found other collaborations, because that we had this need to support and keep our local farmers going. A lot of farmers were growing crops for an industry that was no longer present- the “tourist industry.”

When that wasn't there, a lot of our farmers didn't know what to do with the excess food that they had while at the same time adjusting to the loss of income. That was another thing that we had to consider and figure out is- how are we going to help those guys stay afloat? Luckily for us, we already have a strong backing and support with Kamehameha Schools and HFUU. So that's how we're able to stay there. Between our two organizations, we have a foundation to stand on that will keep us going for a little while, you know, a few years more,

We definitely are working on financial profile expansions. Our farm will take a while to be able to produce so much to sustain itself. So, we needed to find sources to help us sustain ourselves as we develop our farm. So, we have that, but our other farmers don't have it. And that's a big difference already. When we did that, we found Yayoi Hara. She is the daughter of Reverend Hara in Lāhainā's Jodo Mission, and she had a passion to open up a farmer's market during this time. She came to us to find support in helping her promote it, get in touch with farmers, recruitment, and all that kind of stuff. So, we partnered up with her in providing a farmer's market that we still are operating now, every second and last Thursday of the month.

With our Hawai’i Farmer's Union Foundation, we went out and got some other emergency grants available through the CARES Act funds program. And we got one through OHA and one through the Maui County Strong Fund. We catered to our first responders with programs that we manage at our farmer's market. We said, “Hey, with this money, let's make a win-win situation here. Let's cater to our community that is in need and stretched thin, and let's also cater to our farmers which are stretched thin as well.” We developed a program where we made scrips, for the people in this program to go and buy any fresh produce out of our market, which really helped our farmers a lot too.

I’m finding that the farmers that we do have are really strapped and don’t have the time available to be a part of an organization, you know?

Ku'ia Agricultural Education Center photographed by Angie Diaz

I had no idea that you were doing so much it's really incredible. That farmer's market is amazing! You talked about some of the vulnerabilities: that turning point for farmers who had crops that were for the hotels and the need to pivot to find a market, and Lāhainā had a need for a venue to sell fresh local food. Are there other food system vulnerabilities that were exposed to you during this time?

One thing that I want to mention is our community’s dependence on imports. Being in the Farmer's Union for quite some time now and trying to develop a Lāhainā Chapter, I’m finding that the farmers that we do have are really strapped and don’t have the time available to be a part of an organization, you know? Also, there's not much other farming that's specifically catering to the local community, although we have a lot of good gardens going.

When that shut down came, I started watching the stores. Our grocery sections, our vegetable section started to shrink. You'd see a table disappear. Then they narrow it down a little, consolidate, make it more clean and nice, and then another table disappeared. I started thinking, oh, it's only a matter of time before the cost is going to go up really high and it's going to get desperate in town. I'm starting to think for the worst of it, of course, but we held through so far and it seems like we're picking up a lot quicker than everybody predicted we would, back into a regular norm, depending on the system.

I’ve seen pictures on social media of Lāhainā Safeway with empty shelves right now because of the influx in tourism.

Right. So what happened is that the stores had to adjust because the demand had shrunken.

Kaipo, as I'm talking to you, I'm thinking about the land that you're on and what I know about the history of agriculture in Lāhainā. You mentioned that historically it was farmland and I’m curious if that refers to the history of sugar production in the region.

Historically where we are, we've done a lot of research to try and figure out where we were and who we are and what we're gonna do. And we identified our space in Lāhainā to be known as Ka Malu ‘Ulu O Lele. That's history not taught in school. And Ka Malu ‘Ulu O Lele is the name of a large food forest system that took place in our area, in the moku of Lāhainā. And it extended from Launiupoko to just past Māla, and up to around 500 to 700 foot elevation. There's a total of roughly about 10 and a half square miles.

You can find all kinds of beautiful stories about it from both native and foreign testimonies. Newspaper articles and stories that tell about what was present in the time and what people observed. So, we teach that at our farm site, the sense of place, as well as to our farmers, to be well familiar with the area that you farm in. A lot of the things that we noticed with farms, as far as the general farm goes, even if they do organic practices and their best health practices for soil rejuvenation and erosion and all those things, they cover-crop the best they can. However their site doesn't go beyond their farm parameters. At our site, when you come, we speak to that subject. Know your watershed, know your streams, know all of those things that are vital pieces to sustain your farm and those are all identified in the historical properties of our area.

Know your watershed, know your streams, know all of those things that are vital pieces to sustain your farm

That's as light as we'll go on the historical concept of your question. And then as far as the mill goes, the mill came in and, that's another history line, but to remove the food forest system, (I'm sticking to ag), they did three major burnings in the food system. That food system didn't just provide food. It provided the material for housing, provided the material for clothing, and medicine. I'd like to use a fancy word for it, "expressive art" where you get to use dyes and colors from plants that was all found in this food forest system, along with the food provided, you know, the sweet potatoes, the kalo, the ulu, and all the different bananas. All of that is referenced in these logs that we were reading and it kind of gave us the vision for our farming, which wasn't difficult at that point. So, we moved forward.

Ku'ia Agricultural Education Center photographed by Angie Diaz

You know what else we noticed? People who have farmland and have water, but don’t have the time to farm because of the demand of our living on the islands. The cost of living is so high that a farmer cannot sustain himself unless you are fortunate enough to live on your farm.

When I think of West Maui agriculture today, it seems like a food desert. On top of that, you've got all these tourist mouths to feed and empty grocery store shelves.

As I mentioned earlier, the stores started cutting back and they had to adjust to demand. There wasn't the same demand that was present before the pandemic. Food was going bad and getting old, things that we didn't care to eat in our communities weren't moving off the shelf. One of the products that stuck around on the shelves, in the beginning, was yogurt. Maybe our local community doesn’t eat much yogurt? I eat yogurt and my mom and dad eat yogurt, but I don't know. A lot of my friends I grew up with, did not eat yogurt. So we saw that get cut back during the travel restrictions. Now that the visitor rise is in, the demand for yogurt is back and it's gone. All the things that were definitely a higher demand from the tourist industry are wiped clean. I provide food, I grow food, so I'm really paying attention to food.

You know what else we noticed? People who have farmland and have water, but don’t have the time to farm because of the demand of our living on the islands. The cost of living is so high that a farmer cannot sustain himself unless you are fortunate enough to live on your farm. That might make some changes, you know?

Ku'ia Agricultural Education Center photographed by Angie Diaz

The State's budget puts not even 1% towards agriculture, not even half of 1%.

So, we found people who had farmland, and water and very little farming being done. And then all of a sudden, out of a job with a whole lot of time on their hands and everybody's speaking about how important the food is at this moment and how we need to support the industry of ag. I kept telling everybody, yeah, that's kind of crazy, you how much support we've received up until now? The State's budget puts not even 1% towards agriculture, not even half of 1%. So now you hear everybody's screaming about it and I'm all pumped. Cause I'm thinking as soon as we get past this pandemic, everybody's going to be farming. They're going to be pouring in. It's going to be so great.

I hear conversations in my community from family relatives that are in the tourism industry for generations. And they've managed to put in the work and time to establish positions. One conversation went, ‘I realized that I don't need my job and that I can go and do farming and I can live that way". We're having those conversations and I'm so stoked. Awesome.

But now we're back on, and traffic's back up, airplanes are full, car rentals are empty and cousins and families are back at work, back to the grind. And you know, who's really hurting right now? It’s the people who I mentioned that have ag land and have water and they're trying to farm.

They're stretching themselves thin working their 9-5, double shifts, two jobs, if you will. And they're still trying to be able to grow some food. Or those that lost their job, and they were renting. Even though we had that little protection that even if you aren't working at the moment, you can't get evicted from your house, I’ve seen a small percentage of our community end up homeless real quick, and living in tents and living in cars with children. Those are the people that are hurting the most.

I’ve seen a small percentage of our community end up homeless real quick, and living in tents and living in cars with children. Those are the people that are hurting the most.

I stayed home during the shutdown; I didn't drive over to the westside to take advantage of tourist-free beaches but I did catch wind that the houselessness in Lāhainā was visibly increased and that was hard for some in the community.

To be honest, I'm in town a lot, and yes, the homeless population did increase quite a bit. Whether or not they came here during the pandemic and decided to locate in West Maui to be homeless or not, I'm not sure, as far as the increase of numbers. Lāhainā had a serious homeless problem, to begin with. Most of us don't see it because there's a crowd of a different population in the midst as well, which keeps us occupied beyond the scope of seeing what our community is under the lowest layers. You know the deep layers of our community. And I think because that dense population of tourism was gone, we really got to see who was left.

And, then it increased. We try to answer to some of that as a lāhui, as a community. We started to gather resources that we could make use of and put up housing on properties that people had, trying to provide space for a community that we saw rapidly losing their grip for their household. So that was a big one for me. We successfully put up three homes, you know, small little houses. They're houses, they're not big and elaborate of what we find on the market today, but enough to keep a roof over long-time families of our community .

Kaipo Kekona and Rachel Kapu, photographed at Ku’ia Agricultural Education Center by Angie Diaz

As a lāhui we started to gather resources that we could make use of and put up housing on properties that people had, trying to provide space for a community that we saw rapidly losing their grip for their household.

Some of these were on homestead lots, so you didn't have to go through a big, crazy process. It's not going to provide you with a three-bedroom, two-bathroom, and two-car garage, but, you know, you got a roof over your head, strong structure, and shelter from the weather and wind. A nice, comfortable place to rest your head. So, that's what we did. Now, these people are living on the properties that they have, that they were very minimally farming on, and they have their water. Their farming expanded, tripled, in the short time that they had no job. Now that they're back to work, I'm sure that effort will be a little harder to maintain, but now they have a house on their property, and their farming expanded.

I hope they see the potential and opportunity. I've seen it; our community does still have the chance to be more sustainable and dependent on ourselves. That's what I've learned the most, through COVID.

Along that line of positivity and potential- what is your vision for the future? Are there other changes that are happening now, as a result of the pandemic, that you want to stay in place?

Kaipo Kekona and Rachel Kapu, photographed at Ku’ia Agricultural Education Center by Angie Diaz

Let's talk a little bit about the dark side.

You know what, let's talk a little bit about the dark side. So, we’re just getting out of this COVID that slowed everything down, which was, in a way, very beautiful, you know, at least for us here. A lot of us local people, like you said, we didn't go to the beaches, but we saw it. I didn't go to the beaches, but I saw them empty and it felt good. We noticed; I heard people talking about it. I don't even get time to go in the ocean. I was raised diving, swimming, fishing, paddling canoe, and surfing. I don't have that time anymore and I'm gonna make that time. But anyway, I hear from my diving friends, my fishing friends, "ho bradda, fish is way more active, plenny more, you can see ‘em, they out there" and I say, oh, right on. You know, I can't just say that yet myself because it hasn't been that long of a time to give them much space. But apparently, we've seen rapid change in a lot of our resources since this pandemic took place.

Now that we're getting out of it and things are picking up, and even in the midst of it, we've had construction efforts that impact our resources in some of the worst ways, get sped up during that timeframe it seems. When nobody was looking, you know?

Now that we're getting out of it and things are picking up, and even in the midst of it, we've had construction efforts that impact our resources in some of the worst ways, get sped up during that timeframe it seems. When nobody was looking, you know?

When we want to protect our cultural properties and our resources, we go through the proper channels and make the calls. And when you're trying to call these departments in the middle of the pandemic, it wasn't very easy to get through to them. Then when you did get through to them, there was the excuse that they can't be out in the field, they have to work from home, and it’s quarantine time and pandemic is on. So those things are taking place in our community at the same time. Now that we're kind of out, there's more light for a community to see what's happening out there, you know? Those projects have slowed down, but the projects that do work in the light, the bigger, larger projects that are going to be impacting our resources and community, they're starting right back up too.

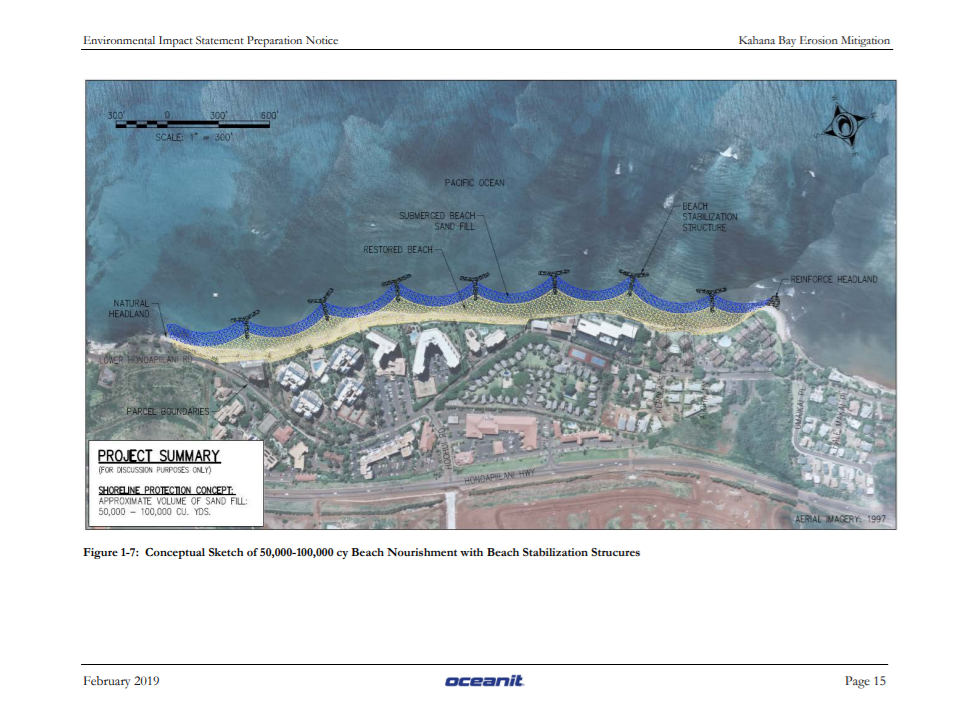

We’ve got the realignment of the lower half of Kauaʻula Stream coming around the corner now. Nobody's really talking about that. And then remember the project about replenishing Ka'anapali Beach, where they want to suck, pump up sand? They did these tests and it reveals that the same sand that they found way out here in 200 feet of water or whatever, is the same sand that is off of the same shoreline that we just tested it from. So, they've mapped out these plots of where the sand is supposed to be, the one that washed away from the beach. And the ocean is a different environment every 10 feet, right? And another ecosystem every 10 feet deep. So, these sands are a hundred feet deep. They want to swallow that up and blow it onto the beach.

They want to bring it back to what it looked like in 1988. I was five years old. All the beaches were different then, from what I see in my baby pictures. They're going to make that come back to that time. That's a lot of sand, and they're now moving that project forward. We're getting all the contacts because these people go through the right channels, and we've made strong efforts to make sure that we formed committees like the Aha Moku Council under the State Department of Land and Natural Resources. It's not like we're just some joke, that people see as another organization in the community, "oh, no, it's just another Hawaiian organization." No, we did the homework and we did the work and now that's where we're at. So, we have these consultation efforts from projects that go through the proper channels. Of course, we don't receive those same consultations with other programs, but we're still there even when those come across the table.

Can I ask you something that's maybe a little bit naive, but is there a way to restore the beaches back to 1988 without removing the hotels?

(Laughing) I don't believe so. There are multiple projects that they want to take place on our end of the Island, the west end. They want to do T-GRIDs out in Kahana, covering a good stretch of the shoreline in front of a lot of the hotels. They want to put all these big pier walls into the ocean, like giant capital T's. They call them T-groins, and they run out in the ocean, straight out. They want to put that up repetitiously along the coastline.

Proposed T-groins from the Kahana Bay Erosion Mitigation Environmental Impact Statement, 2019

That's designed to allow the current and the waves to push sand in and it swirls around in there and it'll settle and then it collects the sand, and it'll happen every so often, you know, have a T-groin. When you fly into O'ahu, I'm not sure what approach you take, but when you're flying past the military bases, along the shoreline, they have one of those projects in place on the military base. And that's been slowly moving forward in our community and we've been expressing our concerns about the impacts that it will have upon the resources that many of us depend on still.

This may not have to go into the EIS report, but mark my words, when they suck up all of that sand out there, they're sucking up little crustaceans, little worms, and all these little tiny guys down there. If you look at the Kumulipo, they tell you way deep in the dark of the ocean, where the little worms move and all of these coral polyps are generating, that's where the beginning of life began.

Then you have the Ka'anapali project that wants to suck up sand from the ocean. Mark my words, this may not have to go into the EIS report, but mark my words, when they suck up all of that sand out there, they're sucking up little crustaceans, little worms, and all these little tiny guys down there.

If you look at the Kumulipo, they tell you way deep in the dark of the ocean, where the little worms move and all of these coral polyps are generating, that's where the beginning of life began. In the Kumulipo. So now they're going to go down there, suck all those guys up, and speed up their process to throw them onto the land. And when they throw them onto the land, you watch, that thing's going to churn up along the shoreline and all those dead skeletons from that sand that they sucked up and threw onto the beach are going to turn into bacteria. And that bacteria is going to end up in the water. And we're going to have a flesh-eating disease, happening right in Ka'anapali, mark my words for it. Watch, I'll bet you a paycheck that that's gonna happen, brah. I'm positive.

The level of human interference is really mind-blowing because some of it seems so obvious. My four-year-old could understand that this is ridiculous. It's money, right? Money is the only thing that could cause someone to not know that this is the wrong thing.

You know how I know why? Because all our other beaches are being eroded due to mismanagement, overdevelopment, and global warming. The beaches that we [locals] use, there's no projects proposed by the state and by these big organizations and agencies; there's nobody's trying to save that beach over there. Everywhere the beach is being “saved” is where the big industries and big hotels are at.

Everywhere the beach is being “saved” is where the big industries and big hotels are at.

Rachel Kapu, photographed at Ku’ia Agricultural Education Center by Angie Diaz

It's impossible to just put up your sea wall or your T-thing; all it does is kick the issue down the shoreline, right?

To begin with, we've changed the coastal line so much that the manipulated shorelines ended up manipulating the currents and tide. Now when the tides rise and the tides drop and the currents are flowing in their natural form, and then they hit this obstructive piece; it's like when you're a kid, and your mom's washing the car and the water's running down the driveway and you put rocks in the middle of the water flow, and you put like your car toy and all these things, and you see the water change and make a different path? We're doing the same thing on the shoreline. That's what we're doing. And people don't want to admit it. Don't want to see it, don't want to say it. But when they did those things, if you look at what happens when you put the rock, the water swirls around behind it, right? It goes around the rock. And then there's this little swirl that takes place, and then the flow goes back to another direction. So that's happening every time. And the more they put out, the more it's going to impact another beach down the road. And then that guy is going to do his effort to save himself, and it's going to affect the next guy down the road.

I know we’ve gotten off of farming, but that's what we're still dealing with. These “collaborative meetings” that they want to have, where they're saying, "Hey, the state's going to be doing this and this, we want to collect your comments". We really have been through this 10,000 times and they collect comments on our concerns, and just wording it where we have no teeth. Feeding a toothless pitbull a piece of steak. So that's the dark side of getting out of this thing.

Oh, they want to say they consulted you, when actually, they just want to use your name.

It was good for a while, because COVID slowed it down and we could really narrow in on some of the projects that still insisted on continuing forward. Construction was still an essential business, so the construction continued moving on during COVID, but it slowed it down a lot. The guys that normally bring in a lot of teams from O'ahu to develop these bigger scale projects, they weren't coming in because we were quarantined right? So that didn't make sense. They'd have to fly these guys in and normally they rent out a house for a week or they go into a hotel for a week and they stay there and they go home during the weekends and then come back for a whole week.

Kaipo Kekona and Rachel Kapu, photographed at Ku’ia Agricultural Education Center by Angie Diaz

We see the companies come back in, the 15 passenger vans on the highway full of construction workers, and we know that the land gobbling up is gonna start right back up again.

So, it slowed everything down. Life was good for a little while. We didn't have to stress as much, and then now it's right back up though. We see the companies come back in, the 15 passenger vans on the highway full of construction workers, and we know that the land gobbling up is gonna start right back up again. Gobbling up our land, just eating it.

There's a prophecy, an olelo no'eau that says wai ai 'āina, "when the water will eat the land," and there's more to this, to the phrase, but I also see that in different perspectives, like, it's not only water that's eating the land, man's eating it. And that's two things that we're dealing with that's increasing at the time. So yeah.

Is a lot of that land agriculturally zoned land that you're losing to gentlemen estates? Fake farms essentially?

Correct. That's how they put it out there, yeah? They gotta put it out so that it's an ag lot and then they sell it off. I mean, just take a topographical look of any of the construction developments in Lāhainā that started in the past 20 years and you'll see real quick that it's built beyond our needs. It's built beyond what we as an island can manage. The men, the humans are eating the land. And that's what I mean by that. So maybe not, wai ai 'āina but kanaka ai 'āina. When the people eat the land, we're not caring for it.

How do you think like the history books are going to describe this time?

I hope it's described as the first awakening; the first light that caused us to open our eyes. Where all of our generations that are stuck into this lifestyle, that we work the nine to five and we still can't afford to live in our own homes. I hope they see that there is a chance, there is a way to control that and it's within us. And I hope that this COVID time is written out, that we do realize that and we all turn over, right? I don't want us to go back and living in grass shacks, but we want to be able to sustain ourselves, and we're pretty close to not being able to do that. I hope in the future, we are on a better path, we're doing much better. and we look back and say that, yeah, COVID was one of those times that really caused a big huli, a big shift in the system. That's what I hope is told.

Agriculture has every single trade available in it. We have plumbing, we have construction, we even have machine operation if we're doing large-scale farming. We have, of course, farming; we have labeling and marketing, packaging, processing. All of that is produced on farms. The more diversified of a system that we have, the more jobs will be needed for various different products. That's what I think we need to focus on politically.

What can people do to help?

We need lobbying done to support agriculture, to put caps on tourism, to make sure that our economy is stabilized by a certain percentage above what it was currently stabilized under other economic functions. We need people to identify what needs to be done to ensure that our economy is sustainable on a wide platform of industries that will be able to continue going without tourists, without the large construction taking place. We need to find out what we're going to do with our economy that will stabilize that. Obviously, agriculture needs to play a role in that.

Agriculture has every single trade available in it. We have plumbing, we have construction, we even have machine operation if we're doing large-scale farming. We have, of course, farming; we have labeling and marketing, packaging, processing. All of that is produced on farms. The more diversified of a system that we have, the more jobs will be needed for various different products. That's what I think we need to focus on politically, that engine, and how are we going to focus on the economy of the state, and figure out how to put more value into the other sectors and balance it out better. The tourist problem. The tourism industry needs to exist. I mean, maybe not needs to, but it will. It's silly to try and just dismiss the whole thing overall, but definitely, we need to look at that through a better management system and practice.

So, those kinds of political points would be great. And then we need people in our community to support more of our local farmers, even if they aren't organic. At that point, at least they're growing something, they have the knowledge to grow it and we can hopefully show them that there is this opportunity in farming practices. I don't even like to say "better" because it's so competitive. You know what I mean? Organic was a beautiful word at one point, and then all of a sudden, organic wasn't good enough. It needs to be regenerative. I'm trying to figure out how do we say those words without having people start to put up walls? We need to keep the community inclusive, as best as possible.

I love that you brought that up. I want to be in the bridge-building, healing the division space. I want to eat organic, but I personally think that we're going to move forward as a community a lot more effectively if we're a little bit nicer about it all.

I'm not going to tell anybody that you can't farm that way or that you can't eat that way, but I will tell them that, I'm sorry, but I'm not going to buy your product; I'm not going to eat your food. But as far as telling them how to farm, I'm not going to tell them how to farm. That's entirely up to them. I mean, in the end we want to try and swing that direction of course, where we're all doing a regenerative effort, for lack of a better term of course, but if we just kicked guys out now because they're farming that way, we're just going to be left with a bunch of us that want to eat organic, but nobody can do it. And then where are we at? We can't afford to put up the walls.

So you want to help? Support your local farmers, man, go get some fresh produce. You don't know how to cook with it? You don't like to eat it? Well, figure it out because that's how it's going to be, you know, once in a while. And then of course, if you want to help personally, come over to the farm and do some work.

Come pull some weeds?

I've pulled a lot of weeds in my life, so I do not like pulling weeds. So, I try my best efforts to not to pull weeds, you know? We'll do a lot of composting and mulching right over the weeds and just mulch them right back in. So you're not pulling them up anymore. Cause, I definitely had my days of pulling weeds. You to go to high school or even intermediate shop class without your shoes on, you get a bucket handed to you and you go fill up the bucket with weeds. That started from sixth grade. Then when I go home, my Dad was ready to have me pull weeds in the yard. So yeah, I hate pulling weeds.

Who have you been inspired by during this time?

My heroes and my inspiration, are the people who find the value in, not the resources of our lands, but the sources of our lands. It only becomes the resource the day we put our hands on it, so we need to identify the difference in that, because that's really where the root's at. People who understand that, doing those energies and taking on those fights - that's the heroes. And the inspiration for me, has been, and always will be, my culture, tradition and my kids that are going to inherit it all.

Kaipo Kekona and Rachel Kapu, photographed at Ku’ia Agricultural Education Center by Angie Diaz