Chantal Chung

Chantal Chung, Mā'ona Community Garden Project Manager, photographed by Ronit Fahl

Unless we really honestly take a look at everything we're producing and all of our processes, we're not going to come up with better solutions. Are we willing to look in the mirror and are we willing to be honest; are we willing to talk to each other? That's going to be the make it or break it moment. The jury is still out on that.

Can you start by introducing yourself and your project?

My name is Chantal Chung, I wear a couple of different hats, but a lot of my work is at Mā'ona Community Garden. We founded that as a group of moms in 2007. It was moms, truly, and it came out of our involvement with a program called Keiki Steps. So, it's administered by In Peace. They are an early childhood program for parents and children together, like a play and learn group. So, we all were doing that at Kahikolu Church in Keʻe. We grew a little garden and started thinking, maybe we could add bell peppers and corn. It was such a wonderful experience for us as moms and our kids to dig in the dirt, we wondered how we could make it bigger? What else can we do?

The opportunity came up in 2007 to rehab the former Wakefield Gardens in Hōnaunau. The original vision of those founders (they were all older, old-school men) was to do this multi-million dollar community center with baseball fields, swimming pools, and a civic center. I was like, "That's really not what the land is saying it wants to be." So, I'd help them set up and do administrative work for them and just kind of circled around. Then, it was really the melding of the two things together. We had access to these 5.4 acres, and us moms were thinking, "What could we do?" Then the financial crisis of 2008 happened. A lot of the backing that the original founders had banked on, the large brokerages, the big developers, they all backed out, So, it was a serendipitous moment (much like COVID is a serendipitous moment) when the funds dried up. Who was left were those that were grassroots, community-based; the others kind of floated off.

It was such a wonderful experience for us as moms and our kids to dig in the dirt, we wondered how we could make it bigger?

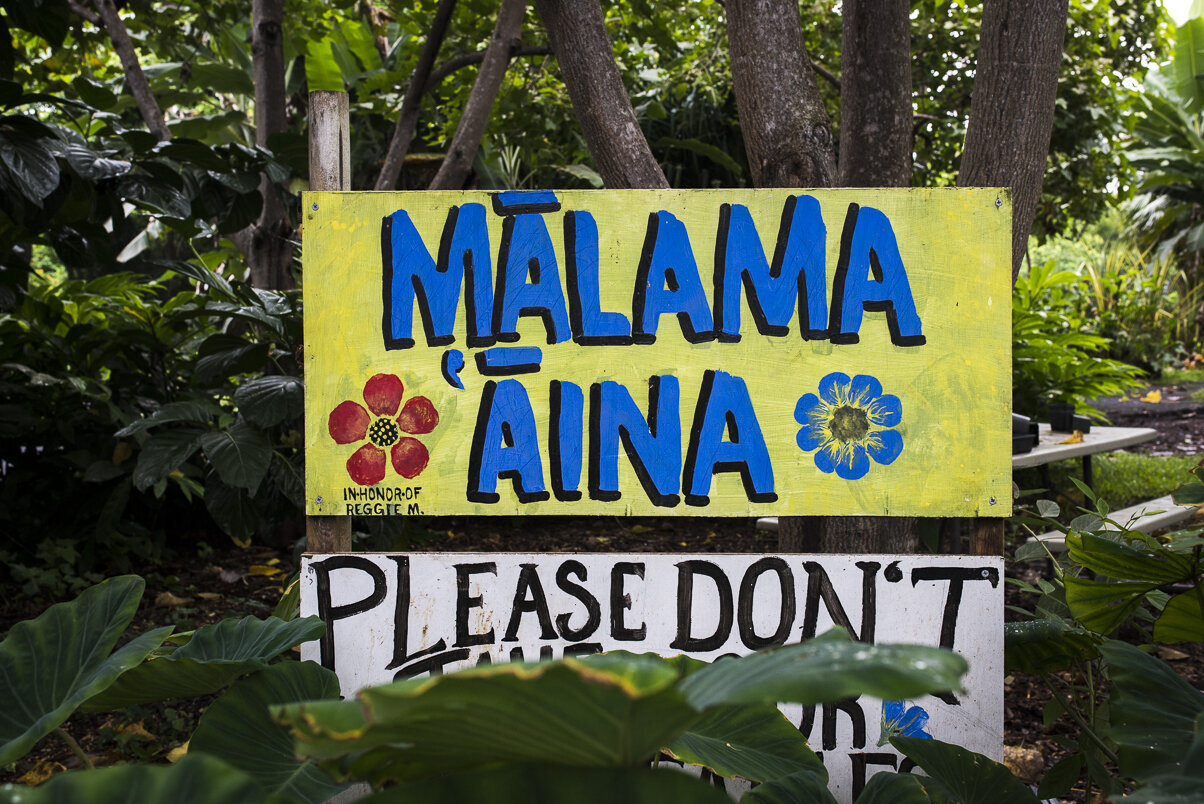

Mā'ona Community Garden photographed by Ronit Fahl

We were left there thinking, "What do we do? How do we make this like our little garden at Keiki Steps, only much bigger?" So, we started clearing, we started taking out the rubbish. There were nine un-permitted structures. We removed over 55 tons of rubbish. Now that was not what we repurposed, not what we composted. We tried to only take out the plastic. There were several families that came and got the wood as we took it apart very carefully, by hand. My mom friends and I were stripping copper in the bushes, to raise our first few hundred dollars, to put fuel into the machines that were helping to clear the land, then recycling cans to afford to bring in a 40-foot container.

Cantor Brothers, Hualalai Mechanical, Young Brothers, and Pacific Waste all contributed their services either for free or at a deeply discounted rate, to help us out with the metal hauling and rubbish removal. Boy Scouts, Cub Scouts, 4H, hula hālau, church groups, school groups, they all came through. A network of women. The husbands, we would drag them along and they'd grudgingly come in with the machine and they're like, "Oh, what do you want now?" All of us would go home and say, "We were thinking," and all of the husbands go, "Are you kidding me?" Or, "We were talking." It was like, oh, poor husbands!

In the beginning, there was a sentiment of, “What is wrong with you guys? Why do you keep spending money on this?” But all of us remembered this place as Wakefield Gardens.

But they've slowly started to see the vision as it's developed. In the beginning, there was a sentiment of, “What is wrong with you guys? Why do you keep spending money on this?” But all of us remembered this place as Wakefield Gardens. It was a beautiful botanical garden, before. It was one of those few free things. Because we didn't grow up rich. Our families didn't have a lot of money. So, our parents always looked for those free things that they could take us to. Here, you could walk through the gardens; they never bothered you. We could sit under the trees. We all have these wonderful memories of that. So, we go okay, let's bring it back. Let's build the soil. Let's clean it and see what can happen. It took us the first four or five years just to clean it.

We started planting trees and then we started planting taro and it grew from there. Then we started having workshops and offering free plots to other people. We're a rural community garden. The difference is, in an urban community garden, not everybody has access to land. They're living in apartments and condos. So, they're looking for access to plots to grow their food. In a rural community garden, most of the people around have access to land. So, what they're looking for is technical assistance. How to's. This was a critical pivot. In the first few years, we figured out very few people are going to want space, but they are going to want to come in here and see demonstrations. So, we started focusing on creating demonstration gardens, teaching how to plant a diverse range of crops.

Mā'ona Community Garden photographed by Lauryn Rego

We try to keep it as diverse as possible because you never know what people were interested in. Reviving traditional crops like kalo and ʻulu, banana, sweet potato, but also gandule beans, achiote, and shiso, all of these old school staples that everybody used to have in their gardens, but kind of died out in the last 30 years.

I'm bringing some of that back and showing people how to use it. A lot of our workshops involve food. So, if we're talking about a particular plant, we'll not only have the seeds available and teach how to plant it but we’ll also cook it. So, people have an experience that engages multiple senses. Also, why would you grow something if you can't cook it?

So that's Mā'ona Community Garden. We do community composting, again, a demonstration to get everybody to be composting at home. The how-to's, and the how-not-to's.

I'll say, "Don't do this." And then I ask, "How do I know this? Because I did it and it did not go well." That humanizes the process so that people don't feel afraid of being wrong. You're not going to do it perfectly. None of us are perfect, but it makes people afraid to try. Then people end up doing nothing because they're afraid to try because they're afraid of being wrong.

I'll say, "Don't do this." And then I ask, "How do I know this? Because I did it and it did not go well." That humanizes the process so that people don't feel afraid of being wrong.

They have that space to come to Mā'ona, try it out, and go home. I have my phone number and email and Facebook posted to the internet, so people know that they can call, email or text if they have questions. So, there’s no reason not to try.

Chantal Chung, Mā'ona Community Garden Project Manager, photographed by Ronit Fahl

I started these interviews about a year ago. and in the beginning, things were happening so quickly. I know, it's hard to look back a year ago, but can you walk me through your experience at that time? What happened at Mā'ona?

We definitely slowed down in some ways, but we also sped up in other ways. We had to focus a lot more on planning because of social distancing. Here's an example, OHA gave us a small grant to do workshops. We thought, okay, we're going to do this, but how are we going to do it safely? So, it took us sitting down and figuring out the puzzle of, okay, how do we maximize social distancing and safety, but also maximize learning. So, we came up with a new format.

We did a workshop, on a subject, like say composting. We did two days in a row, Saturday and Sunday. Saturday morning from nine to noon, we would host one group of eight to ten, at separate tables, with separate kits of materials. At the end they go, "Can we help you clean up?" Like, "Nope. Get out." Then we'd sanitize every surface. We kept them corralled in one area, I felt so bad, telling them, “No,you can't leave, you can't touch anything.” They all kind of got it. So then we tell him, "Go, leave, take your produce.” We were distributing individual paper bags of local produce.

So, then we sanitize, reset and the next group would come in from 1:00 PM until 4:00 PM. Same thing, same workshop. After they'd leave, we’d sanitize everything and duplicate that process the next day. So, we did four groups in a weekend, eight to 10 each, to hit the 32-40 people we would normally do in one workshop. So, it was a lot more labor-intensive.

Was the OHA grant was something you were awarded before COVID and that you were trying to fulfill, or was it a direct result of their response to COVID?

As a direct response; we were invited. We saw this bloom of funding available, which was great. We were able to do quite a bit with it, I think it was $9,800. We did four workshop weekends. So, that's about 160 people, give or take. Then we also were able to engage with the social media content creator, and he was able to make our digital content, that's where you see that expansion of our Instagram presence. We're experimenting with outreach because a lot of people are just stuck at home. We started experimenting with short videos, we're still doing that. How do we get out nuggets of information in bite-size pieces? So as not to overwhelm, but also take advantage of the large audience. Internet and social media usage have gone through the roof during this pandemic. So, how do we capture attention to inform, educate, and empower?

Chantal Chung, Mā'ona Community Garden Project Manager, photographed by Ronit Fahl

What you do need to know about what we do is- it is actually illegal.

It's effective. I've been following, for a long time, but most recently, I've seen a lot of waste diverted and an emphasis on cardboard and building soil from it, which is pretty incredible. Do you want to talk about that? It seems like a huge accomplishment.

The community composting effort is something that we've done since the very beginning. We hand sorted all of that rubbish that we took out of the ground and those nine un-permitted structures. People were just dumping their trash in holes in this beautiful place. I was just like, oh my gosh, what do we do? So we started composting small-scale and then our neighbors needed a place to bring green waste. We started doing that small scale. What is the number one thing thatSouth Kona farmers will say they don't have enough of? Soil. They will all tell you, “We're on solid rock.” Okay. This seems like it's a need, let's figure out how to do this. Then we became more and more aware of the waste issues with our landfill, especially in the last few years with the Hilo landfill closing. I don't know if you're aware, but they're now trucking Hilo's waste to the West side.

So, how can we do better? So the community composting project is a proof of concept project. What you do need to know about what we do is, it is actually illegal.

Please tell me all about the illegality of composting today.

Okay. So, it's happening on several different levels. Foremost is on the Department of Health level. I agree with taking a firm stance on making people conform. So, in California, there's something called tiered composting. So, there are different levels, right? There are the big boys, which includes large-scale composting, landfills, things like that. But if you're only dealing in tiny buckets of green waste and food waste from your community, tiered composting is meant to enable the smaller composters, the community composters. In New York, there's community composting going on and it's supported by the municipalities. There’s the California Composting Council, CCC that gives mini, operational grants to their small community composters. It's a community that wants to do better with its waste.

Everybody wants to do better with their waste. Really, it's the rare person who's like, "Nah, I don't care." They're just distressed by how much waste that we're making, but they don't know. They just know “away”, I want it to be thrown away and dealt with. A lot of people don't understand the mechanisms that go into processing waste, as a County, right? As a collective. What does that look like? There are all the rules, policies, and regulations, There are EPA rules. For good reason, because one of the biggest risks of composting is you're going to become a vector for pathogens and you're not going to do it properly. You're going to become a vector for invasive species, fire ants, semi-slugs, and you're going to create a dangerous situation by not doing your due diligence. That's what the regulations are there for. However, the Department of Health doesn't have enough staff to go and regulate all of this.

Photo by Lauryn Rego

The main objection from the Department of Health is: "If we allow all this community composting, we won't have the staff to go out and regulate it." So, that's a problem that needs to be solved.

The main objection from the Department of Health is: "If we allow all this community composting, we won't have the staff to go out and regulate it." So, that's a problem that needs to be solved. There has to be outreach and education dollars accompanying increased staff funding and the opening up of community composting. Because you have people that, in all of their good intentions, are not going to do things properly. They're not going to do their research. “I just put some stuff in a pile on the ground and boom kanani, compost!” No, there are ways to do it so you don't actually pollute the water table, pollute the air, introduce heavy metals, chemicals, and all those things into the soil.

It's a delicate balance. I believe deeply in regulation, but also research to discover if that regulation is enabling or disabling and how we could improve it. Communication and the education of not only policy makers, but the community as well. If we focus only on community education, then we've got a whole bunch of well-educated community members who can't do anything because the policymakers are not educated. The Farm Bureau opposed one of the composting bills. Why? I can send you the email. Because it said it would take away from the pig farmers. But do pigs eat lemon peels? No. So, everyone's looking for this all-or-nothing approach. You have to look at the whole picture.

I have so much deep appreciation for you breaking it down like this, in such a clear way. And I think that that's really important. As you're talking, I'm curious how sending it all to the one landfill is the solution. How does the landfill mitigate the risk of being a vector?

I know right? They don't. Not to mention the outdated and leaking liner that goes straight to our natural marine environment.

So it's crazy. Okay. I just wanted to make sure I wasn't missing something big there.

Doesn't it feel like you are? Doesn't it, at every step? I'm like, I'm missing something here. Do I need to slow down and understand a little bit? Nope. The more I dig into it, the more questions I have.

This post-COVID recovery feels like a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to get it right. And I don't know that we're getting it right. I would like like this project to play a small role in helping illustrate some of this, directly to policymakers.

Chantal Chung, Mā'ona Community Garden Project Manager, photographed by Ronit Fahl

This is how we get it right. We start communicating with one another. Start collaborating. We start breaking down the silos that have held us apart. What if the Department of Health were to be engaged as a partner, valued as a regulator and a protector of the safety of all of us?

This is how we get it right. We start communicating with one another. Start collaborating. We start breaking down the silos that have held us apart. What if the Department of Health were to be engaged as a partner, valued as a regulator and a protector of the safety of all of us? Value that, work with them, have a process that everybody comes to the table and says, "Hey, I'm gonna lay it all out right here. This is the piece of the puzzle that I bring." And then the next person over goes, "This is a piece of puzzle. These are my challenges. These are my concerns." And having that honest, open, equitable conversation.

Instead, what goes on right now is backbiting and drama, because all of these little organizations and non-profits are competing for funding. They're competing for the attention of legislators. My bill, my legislation, my contact. That is what's holding us back. So, of the multiple composting bills that there were, were the legislators introducing those talking to each other? Nah. Were the nonprofits or organizations and agencies backing those bills, talking to other each other? Nah. Were they thinking in terms of community-based economic development, environmental sustainability, and social equity altogether as one? Nah, they were still in their silos, still fighting one another. This is what dooms all of these things to failure.

And you can print that exactly how I said it.

I would love to print that exactly how you said it. because somebody's got to say it.

Achiote seed at Mā'ona Community Garden, photographed by Ronit Fahl

There was one meeting that I went to with a group of mostly women, who had gotten together to do zero waste. This big cheese person from a larger non-profit comes in, and because nobody's doing what she says to do, she says, "You were just a bunch of moms making soap before I came into the picture." It hit me so hard. This is another woman, downing on other moms. It hurt me because Mā'ona was started by moms and that's what the old men said to us, "Yeah, go ahead you girls, do what you want to do." Like, "Eh, you're going to fail. So, go." Moms are important. Moms, get it done, right?

And it's empowering other moms to feel like, "Oh, I could do that." That's the feeling you want to end with from every call and every interaction. I want people to walk away from me, at all times, with that feeling of, "I can do that!" Not, "Oh, I'm dumb or I can't," or "I made an ass out of myself." No, don't be embarrassed. Ask me any kind of questions you want. The worst I'll say is, "Nah, nah, nah," but I'm not going to squelch anybody, because I want people to walk away from every interaction, especially walk away from Mā'ona and feel like, I can do this. Right now, I walk out of a lot of these meetings and I feel crushed and I have to recuperate because there's so much drama.

We have all of the resources we need to grow all the food we need, have all of the water we need, and manage all of our waste right here on island. Coming at it from a feeling of empowerment and a feeling of abundance, rather than that constant fear and feeling of scarcity that so many people apply to food systems.

I'm jumping around a little bit. but to back up in case we didn't cover it, are there any other food system vulnerabilities that were exposed for you during this time?

Transportation and logistics. I realized that, many of us did, are the problems in our food system, the problems in our waste systems, the problems in our communities are often can be boiled down to logistics. Just planning, knowing how something gets from point a to point B and back again. That's systems thinking, right? Our waste management is a logistics problem. We have all of the resources we need to grow all the food we need, have all of the water we need, and manage all of our waste right here on island. Coming at it from a feeling of empowerment and a feeling of abundance, rather than that constant fear and feeling of scarcity that so many people apply to food systems. “We don't have this.” Yeah, we do. Slow down. Figure out where that something is. If we don't have it, maybe we don't need it. Just saying. If you're banging your head against the wall, it might be time to use that wall to rest on, re-tool and come back at it. The biggest nexus is logistics.

There's an effort going on right now, through the Hāmākua Institute. They're basically mapping the food systems along with Hawaiʻi Island Food Alliance, HIFA. The whole idea is, how are we going to find the bottlenecks and how are we going to define the problems? If we don't have the right information, we can ask these questions all day. So, we want to examine all of our unexamined assumptions. Because sometimes, when you put it all out there and you look at the pieces of the puzzle on the table, you realize, "Oh, that's why that hasn't been working! Because it's missing this." But until you collect that data, you're not going to know.

Waste management is the same thing. Every system is the same until you really honestly do an audit. What is, what was, you put those two things together and with what could be. That's the end, what could be. Until you know what is, and what was, you're not gonna be able to come to what could be. You're not gonna move forward because you need to keep on cycling back around because you haven't examined. It will just keep repeating.

Mā'ona Community Garden, photographed by Ronit Fahl

We're going to double food production by 2030, but I’m not sure there is a real baseline for how much food we are producing anyway.

Well, there is kind of a baseline, but there are no concessions made or plans for how we're going to do that. You also have to plan for how are we going to process all that food and where the waste is going to go. In 2019, we diverted 30,000 pounds of food processing byproduct from the Hawaiʻi ʻUlu Producers Cooperative. Not one pound of their food waste or their paper waste as ever gone to the landfill, since their beginning in 2016.

This is possible with partnership and planning. It was part of their business plan to not be a polluter. So, instead of seeing their waste products, as rubbish as to be thrown away, they're looking at their waste products as being components of another value-added product, components of how we grow more food. It's the shift in thinking that needs to happen with a lot of these productions.

Unless we really honestly take a look at everything we're producing and all of our processes, we're not going to come up with better solutions. Are we willing to look in the mirror and are we willing to be honest; are we willing to talk to each other? That's going to be the make it or break it moment. The jury is still out on that.

Let's let's talk about your vision for the future. What do you want to see? I'm worried we're bouncing back and not forward, so we’ve got to keep visualizing.

I believe deeply that the way forward exists in cooperative effort. The County operates the Hawaiʻi Island Food Alliance out of the Research and Development department. That particular effort provides a platform for us to come together, once a month. It's a diverse group of food systems stakeholders, organizations, entities, and efforts. We plan a summit every year, but I strongly believe in the consortium approach, the cooperative approach. How is it that we're tying together stakeholders all along the value chains of food, of waste, of energy -- and having them work together not only on, on-the-ground operations, but planning for the future. Assessment, data collection, policymaking, how are we stringing together the pearls?

How do you think this time is going to be described in the history books of the future?

The Great Pause. This pause has allowed a lot of us to break out of our daily routine. Things go along and you don't really think about things because you're on your track, right? I go to work, I come home, I do my project, I do this, and you're not really thinking about anything outside of that. But this time has given us a chance to pause, to think, to really be able to process the multiple layers of information all around us, to be able to make that choice to pivot and to make different choices. To understand when you're in your daily routine, you're not aware of your choices. Oftentimes, you're unaware of how destructive, or unhappy you are, because you're doing your thing. I don't know if it's adrenaline or it's being overwhelmed, but you're locking out a lot of the experience of life.

You're not letting that the richness of the tapestry around us in, for good or for ill. You're not just not seeing and you're just going. This particular time has stopped the go, go, go. We've been forced to sit and think. Sit in our decisions and really reflect. So, it's great. I like to call it the great pause and pivot.

How can people help? What do you need?

I need people to want and be willing to collaborate with each other as community members. Show each other a little love, talk to each other a little bit, get over yourself. I would like organizations, agencies, and institutions as well, to get over themselves, sit, and really honestly have that conversation.

It's my greatest hope that what will come out of this thing is that in this time of reflection, in this time of pause, we are able to see ourselves for what we really are and what we could be and what the bridge between those things are. That's what I want.

Is there anybody you want to shout out that has been inspiring to you during this time?

So many, but I would definitely say the ʻUlu Producers Cooperative and the Hawaiʻi Island Food Alliance. There's like 10,000, but those are my top two.

Chantal Chung, Mā'ona Community Garden Project Manager, photographed by Ronit Fahl